The Colt Peacemaker: History, Legacy, and the Revolver That Defined the American West

Share

Introduction: The Legacy of the Colt 1873 “Peacemaker”

Denix Piecemaker 1873 Non-Firing Replica Revolver

Denix Piecemaker 1873 Non-Firing Replica Revolver

In the long and often romanticized saga of the American West, no firearm looms larger in myth and memory than the Colt Single Action Army revolver, more famously known as the “Peacemaker.” Introduced in 1873, this six-shot revolver was not merely a weapon—it became a symbol. Carried by soldiers, settlers, lawmen, outlaws, and cowboys alike, it earned a reputation as one of the most reliable and practical handguns of the nineteenth century. Its adoption by the U.S. Army, followed by its widespread civilian use, cemented its place as one of the most consequential firearms ever manufactured.

The Peacemaker’s enduring fame lies not just in its technical achievements or widespread use, but in its profound cultural resonance. It was a companion on horseback, a sidearm in dusty saloons, and later a fixture in countless dime novels, Western films, and TV serials. It was wielded by historical figures whose names became folklore, from lawmen like Wyatt Earp and Pat Garrett to outlaws like Billy the Kid and John Wesley Hardin. The revolver’s very silhouette—the long barrel, the swept-back hammer, the distinctive crescent trigger guard—has come to embody the entire era of westward expansion.

Yet beyond the myth lies a real and intricate history. The story of the Colt 1873 is not just one of rugged individualism or frontier justice. It is also a story of American industrial ingenuity, military innovation, changing ballistic science, and the deepening divide between black powder and smokeless technology. Over the decades, the Peacemaker evolved in both form and function, spawning numerous variants tailored to the needs of soldiers, civilians, and sport shooters alike.

Today, though the original revolvers are now museum pieces or collectors’ treasures, the legacy of the Peacemaker lives on in faithful reproductions. Companies like Denix and Bruni produce historically accurate non-firing and blank-firing replicas that echo the design and feel of the original Colt. These replicas, often used in film, reenactments, and displays, help preserve the legacy of the Colt 1873 in a modern world that is still fascinated by the age of revolvers, saloons, and wide-open frontiers.

This article will explore the complete story of the 1873 Peacemaker—from its inception and military service to its cultural legacy and modern reproduction. In doing so, we will separate fact from legend and bring to light the true engineering and historical significance of one of the most iconic handguns in American history.

Design and Development of the Colt 1873

Photo courtesy of Gunsweek.com

Photo courtesy of Gunsweek.com

The Colt Single Action Army revolver was born from a critical moment in the evolution of firearms technology. In the aftermath of the American Civil War, the United States military found itself at a crossroads. The cap-and-ball revolvers that had served during the war were rapidly becoming obsolete, outpaced by the emerging world of metallic cartridge firearms. Reloading black powder revolvers was a slow and messy process, often ill-suited to the fast, close-quarters violence of cavalry warfare or frontier skirmishes. The Army sought a revolver that could fire modern ammunition, operate reliably in harsh conditions, and serve as a standard sidearm for decades to come.

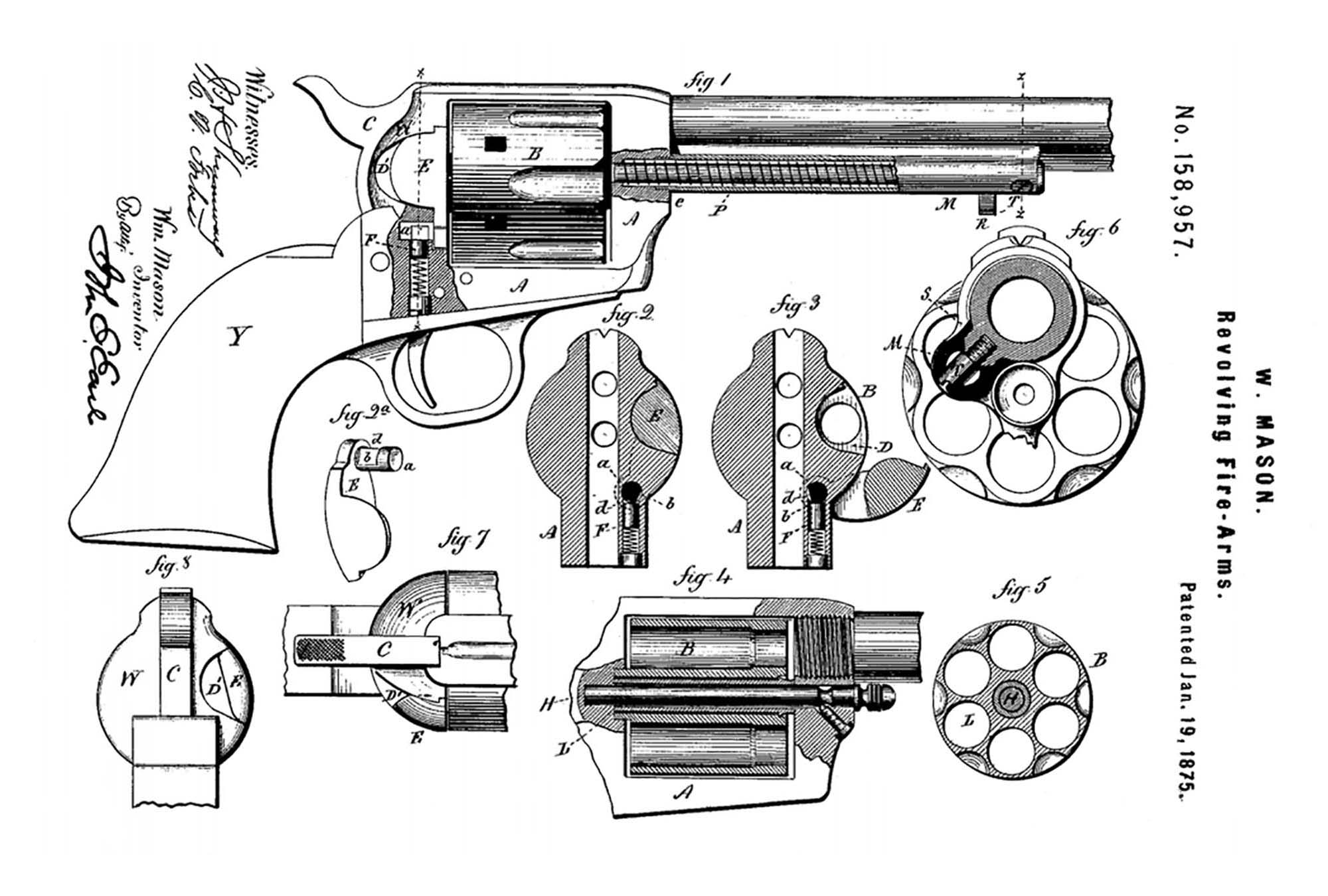

Enter Colt’s Patent Firearms Manufacturing Company. The Connecticut-based company was already renowned for its earlier revolver models, including the 1851 Navy and the 1860 Army. However, to remain competitive, it needed to fully transition from percussion-fired arms to metallic cartridge revolvers. Two of Colt’s most important engineers, William Mason and Charles Brinckerhoff Richards, were tasked with this challenge.

Mason and Richards had already worked on converting older cap-and-ball revolvers to fire metallic cartridges—interim solutions that helped keep Colt in the game while it developed something new. These conversions, often referred to as the Richards-Mason conversions, were clever but ultimately limited by the structural constraints of the original black powder frames. A fresh design was needed—one that took full advantage of modern ammunition and manufacturing capabilities.

Their work culminated in what would become known as the Colt Single Action Army revolver. The design featured a solid frame with a top strap over the cylinder—an element that significantly improved structural integrity and durability compared to the open-top designs of earlier revolvers. It was a six-shot, single-action revolver chambered for the powerful .45 Colt cartridge. Loading was accomplished through a side gate on the right-hand side of the frame, and empty shells were ejected individually with a spring-loaded ejector rod mounted beneath the barrel. The revolver operated with a single-action mechanism, meaning the hammer had to be manually cocked for each shot, which contributed to both its mechanical simplicity and its legendary reliability.

The Army tested Colt’s new revolver in 1872. Competing against designs from Smith & Wesson and Remington, Colt’s revolver impressed military evaluators with its rugged construction, accuracy, and ease of maintenance. On January 15, 1873, the U.S. government officially adopted Colt’s new revolver as the standard-issue sidearm for the Army cavalry. The initial order called for 8,000 units, all chambered in .45 Colt and fitted with long 7½-inch barrels.

The choice of the .45 Colt cartridge was no accident. It was designed in tandem with the revolver itself, offering tremendous stopping power. Loaded with 40 grains of black powder and a 255-grain bullet, it generated impressive muzzle energy and became known for its ability to incapacitate a target with a single well-placed shot. For soldiers engaged in mounted combat or frontier patrols, this kind of firepower was essential.

Despite being designed for war, the Colt 1873 was also engineered with an eye toward practical field use. Every detail—from the hammer spur’s reachability with a gloved hand to the frame’s ease of disassembly—reflected the realities of combat conditions. Durability was a central concern; Colt revolvers were expected to endure rain, sand, and hard use without failing. Over time, this battlefield resilience translated into the revolver’s popularity among civilians, many of whom came to view the gun as a personal insurance policy on the unpredictable frontier.

Although it began as a government weapon, the Peacemaker’s design was flexible enough to evolve with civilian demand. Within just a few years of its adoption by the military, Colt was already producing the revolver in multiple barrel lengths and eventually in a variety of calibers. The framework had been laid for a revolver that could serve anyone—from cavalrymen to cattlemen—and in doing so, it became the archetype of the American revolver.

Military Service and Frontier Use

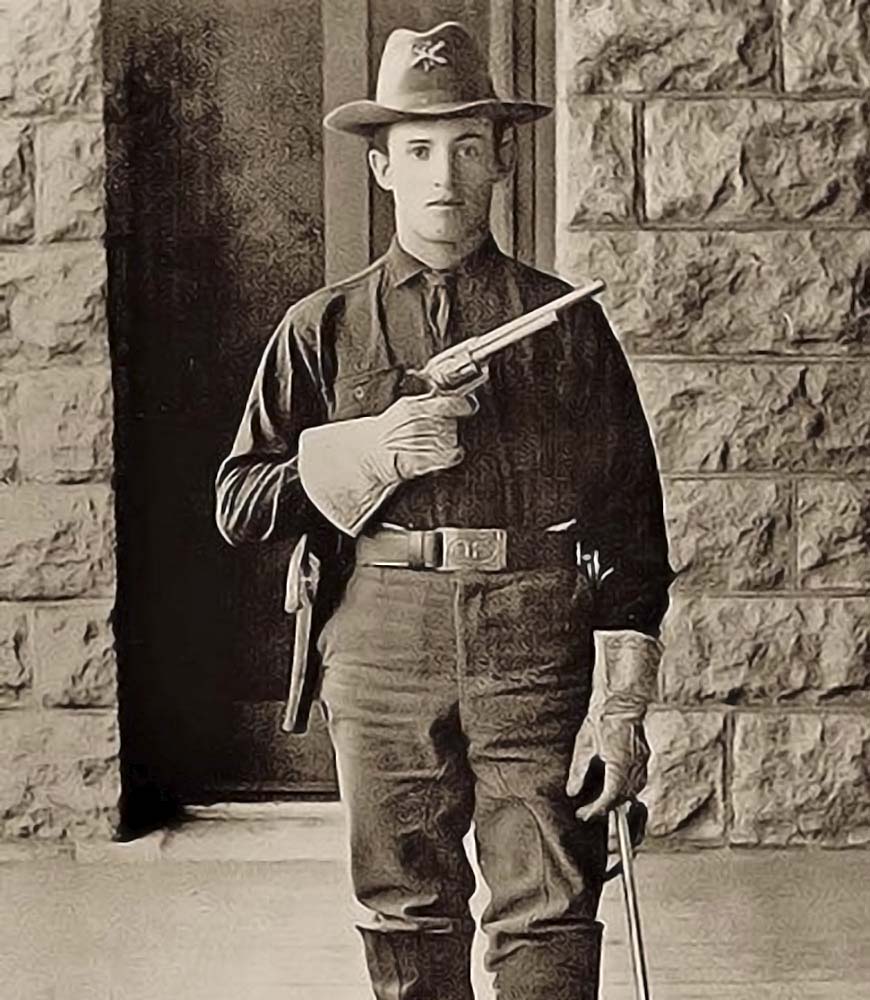

Cavalry Soldier and horse at Fort Union, New Mexico with Colt 1873 SAA (Photo: National Park Service)

Cavalry Soldier and horse at Fort Union, New Mexico with Colt 1873 SAA (Photo: National Park Service)

From the moment it entered U.S. military service in 1873, the Colt Single Action Army became more than just a weapon — it became an extension of the soldier, a sidearm whose reputation for reliability quickly spread beyond the ranks of the cavalry. Initially, the U.S. Army placed a substantial order of 8,000 units, each with a 7½-inch barrel and chambered for the powerful .45 Colt cartridge. These revolvers were primarily issued to mounted troops, where quick-drawing ability and mechanical durability were paramount.

For nearly two decades, the Colt 1873 served as the Army’s standard-issue sidearm, seeing action during the height of the Indian Wars and in countless conflicts across the expanding American frontier. Soldiers valued it for its ease of use and simple maintenance. The single-action mechanism, though slower to fire than the newer double-action designs, offered a deliberate and accurate method of shooting that suited both military discipline and the practical needs of life in the field.

In this rugged theater of operation, the revolver’s robust construction proved invaluable. It could be fired and maintained in harsh, remote environments with limited access to proper gunsmiths or spare parts. When kept reasonably clean and oiled, the Peacemaker would fire consistently and with substantial power, capable of disabling a target—animal or human—with a single well-placed shot.

One of the Peacemaker’s most notable historical appearances occurred at the Battle of the Little Bighorn in 1876. Elements of General George Armstrong Custer’s 7th Cavalry carried the Colt SAA into battle against a coalition of Lakota, Northern Cheyenne, and Arapaho warriors. Though the defeat of Custer’s forces remains one of the most significant military failures in U.S. history, it also underscores the era in which the Peacemaker was a frontline military weapon. Many of the revolvers recovered from the battlefield bore the inspection markings of Orville W. Ainsworth, the government inspector assigned to oversee the earliest military production of the Colt 1873.

As the 1880s progressed, the Army began exploring newer revolver designs that offered faster reloading and double-action firing. The Smith & Wesson Schofield, for instance, introduced a top-break mechanism that allowed spent cartridges to be ejected all at once — a feature that the Colt, with its one-at-a-time ejector rod system, lacked. While the Army experimented with such alternatives, it continued to issue the Colt SAA in significant numbers well into the 1890s. Eventually, in 1892, the Colt was officially replaced by the .38 Long Colt double-action revolver. Even then, many troopers preferred to retain their older .45s, particularly in field assignments where raw stopping power and simplicity were still valued over modernity.

Parallel to its military service, the Colt 1873 was making its name known on the civilian frontier. Released for civilian purchase shortly after its adoption by the military, the Peacemaker quickly found favor among settlers, lawmen, miners, and cowboys. It offered a dependable sidearm in a lawless and often violent world. Law enforcement figures like Wyatt Earp, Bat Masterson, and Pat Garrett are closely associated with the Peacemaker, using it in both documented encounters and countless retellings through newspapers, books, and films.

The revolver’s appeal was further enhanced by its compatibility with popular rifle cartridges of the time. In 1878, Colt introduced a variant chambered in .44-40 Winchester, the same caliber used in the Winchester Model 1873 lever-action rifle. This allowed a person to carry one type of ammunition for both their sidearm and their long gun — a practical and economical solution, especially for those traveling long distances across the plains, deserts, or mountains with limited access to ammunition resupply.

Throughout its military and civilian life, the Colt 1873 served in roles that extended well beyond traditional combat. It was a companion during cattle drives, a protector in remote mining camps, a badge of authority for sheriffs and marshals, and a deterrent in personal disputes. The revolver’s mere presence was often enough to prevent violence, and when violence did erupt, it was a tool that could be trusted to perform.

By the time the Peacemaker was formally retired from frontline military service, its reputation was already cemented. It had proven itself not only as a sidearm of war but also as a tool of survival, law enforcement, and personal defense in an unforgiving and rapidly changing America. It was not just a gun carried through history — it was a gun that helped make history.

Photo courtesy of Gunsweek.com

Photo courtesy of Gunsweek.com

Variants and Technical Evolution

While the Colt Single Action Army revolver remained visually consistent throughout much of its life, its internal mechanics, caliber options, and special-purpose variants evolved considerably over time. This adaptability was one of the reasons the Peacemaker maintained its relevance for so long. It was not just a product of its time, but a design that Colt refined and diversified in response to military feedback, market demands, and the emergence of new technologies in the firearms world.

One of the most significant areas of variation in the Colt 1873 was barrel length. The original model, issued to the United States Cavalry, came with a 7½-inch barrel, chosen for its balance between accuracy and stopping power. This long-barreled version offered an extended sight radius, which benefited mounted troops firing at greater distances. However, as the revolver gained popularity among civilians, law enforcement, and others who needed a more compact sidearm, Colt introduced new lengths. The 5½-inch barrel, commonly referred to as the Artillery Model, became a favored compromise—shorter than the cavalry model but still long enough to retain strong ballistic performance. Eventually, a 4¾-inch variant, often known as the Civilian or Gunfighter model, was released. It proved especially popular among lawmen and gunslingers in the American West for its ease of draw and more compact profile.

There were even shorter-barreled versions produced in limited numbers, typically between three and four inches in length. These models, often lacking an ejector rod due to their abbreviated design, were marketed as Sheriff’s Models or Storekeeper revolvers. They were intended for discreet carry and quick deployment in close-quarters situations. Although not mass-produced at the same scale as their longer-barreled cousins, these compact revolvers found favor with gamblers, city marshals, and others who needed a powerful sidearm that could be easily concealed.

Another major dimension of the Peacemaker’s evolution was its expansion into multiple calibers. Initially, the revolver was chambered solely in .45 Colt—a round that was developed in concert with the revolver itself and chosen by the military for its remarkable stopping power. Over time, however, Colt responded to civilian demand by offering the revolver in a wide range of calibers. One of the most popular was the .44-40 Winchester, introduced in 1878. This caliber was already widely used in the Winchester Model 1873 lever-action rifle, and its introduction into the Colt SAA meant that a user could carry a rifle and revolver that shared the same ammunition—a considerable advantage in remote or combat-prone territories.

Other calibers followed, including .38-40, .32-20, .41 Colt, and even .22 rimfire, each catering to different needs and preferences. In total, Colt offered the Single Action Army in over 30 different calibers during its production history. This made the revolver not only versatile but also uniquely customizable, appealing to a broad spectrum of users—from ranchers and farmers to sports shooters and lawmen.

As black powder gave way to smokeless powder in the late nineteenth century, the Colt SAA underwent a significant structural enhancement. The original revolvers, known as black powder frames, were constructed with the material strength necessary for the lower pressures of black powder cartridges. However, smokeless powder generated higher internal pressures and demanded a sturdier frame. In response, Colt introduced the smokeless frame near the turn of the twentieth century. These frames were slightly thicker, built with stronger steel alloys, and could safely handle the increased power of modern ammunition. Though outwardly almost indistinguishable from the earlier frames, the smokeless models were a major step forward in the revolver’s technical evolution.

Mechanically, one of the most important changes came in 1896, when Colt altered the way the cylinder was retained within the frame. The earliest Peacemakers used a single screw to hold the cylinder pin in place—a secure but somewhat cumbersome method when field stripping the revolver. After 1896, Colt replaced the screw with a spring-loaded crossbolt, which allowed for much easier cylinder removal and maintenance. This seemingly small modification reflected Colt’s ongoing efforts to improve the revolver’s field utility without sacrificing its core design principles.

Other refinements included alterations to the ejector rod head. Early models featured a large, round ejector button, often referred to as a bullseye ejector. This was later replaced with a more streamlined crescent-shaped ejector, which provided a better grip and allowed for faster, more intuitive case extraction—another nod to the practical needs of users who might have to reload under pressure.

Over time, Colt also introduced specialty variants of the SAA, catering to specific markets and applications. The Flattop Target Model, produced between 1890 and 1898, featured an adjustable rear sight and was designed for competitive shooting. Another notable variant was the Bisley Model, introduced in 1894. Named after the famous English shooting range, the Bisley featured a redesigned grip frame, a wider trigger, and a lowered, broader hammer spur. These changes were tailored to the needs of target shooters who preferred a more upright hand position and a faster hammer reach. Though not as aesthetically iconic as the standard Peacemaker, the Bisley was popular in its own right and became especially well-regarded among marksmen.

Throughout its life, Colt also produced engraved, commemorative, and limited-edition models, including ornate revolvers presented to heads of state, lawmen, and exhibition shooters. These collector-grade revolvers were often embellished with scroll engraving, ivory or pearl grips, and gold inlays. While they may have spent more time in velvet-lined cases than on saddle holsters, they speak to the Colt 1873’s status as both a tool and a symbol—equal parts utility and legend.

Taken together, the many barrel lengths, calibers, frame types, and mechanical tweaks that defined the Colt Single Action Army’s production run tell a story of a firearm that never stopped adapting. The revolver’s basic form—a six-shot, single-action revolver with a loading gate and exposed hammer—remained steady, but within that frame, Colt found countless ways to meet the changing needs of soldiers, civilians, sport shooters, and collectors alike. It is this blend of constancy and innovation that allowed the Peacemaker to survive not just as a relic of the past, but as a continually relevant tool for nearly a century.

Cultural Legacy and Famous Carriers

Wyatt Earp Buntline Special (although not confirmed, based on stories, it is believed that he carried one)

Wyatt Earp Buntline Special (although not confirmed, based on stories, it is believed that he carried one)

As the 19th century gave way to the 20th, the Colt Single Action Army had already become more than a revolver. It was a symbol of American identity, a tangible artifact of westward expansion, personal independence, and frontier justice. Its silhouette had been etched into the collective imagination of a country in the midst of defining itself. Though its official military role waned by the early 1900s, its cultural impact was just beginning to take root.

The Colt Peacemaker’s most enduring legacy is perhaps its role as the quintessential firearm of the American West. Carried by an astonishing array of characters, both historical and legendary, it was wielded in dusty streets, courtrooms, saloons, and battlefields. It became so synonymous with the image of the frontier gunfighter that even those who carried other weapons were retroactively depicted with a Peacemaker strapped to their hip.

Among the most famous lawmen associated with the Colt 1873 was Wyatt Earp, a figure immortalized in both historical record and Hollywood myth. Earp reportedly used a long-barreled Colt, sometimes referred to as the “Buntline Special,” a model rumored to have been gifted to him and other lawmen by dime novelist Ned Buntline. Though historians debate the accuracy of this claim, the association between Earp and the long-barreled Colt became a cornerstone of his legend, especially after the publication of his biography in the early 20th century.

Bat Masterson, another frontier lawman and gunfighter, was also a documented owner of multiple Colt revolvers, often ordering them directly from Colt’s factory with custom features such as pearl grips and special finishes. Masterson later transitioned into journalism and politics, but he never entirely shed his image as a man who lived by the revolver in his early days.

On the opposite side of the law, figures like Billy the Kid, Jesse James, and John Wesley Hardin were associated with the revolver through their violent reputations and the tales that followed them. Whether these men always carried a Colt 1873 or occasionally used other firearms is sometimes unclear, but the Peacemaker became the symbolic weapon of choice in stories passed down from one generation to the next.

Beyond the personal firearms of lawmen and outlaws, the Colt 1873 achieved a larger-than-life status through its portrayal in popular media. In the early decades of the 20th century, the revolver began appearing in Western films, first in silent cinema and later in full Technicolor productions. Its visual distinctiveness, with its long barrel, deep blued finish, and wooden grips, made it instantly recognizable. Filmmakers frequently placed it in the hands of protagonists and villains alike, reinforcing its role as the weapon of the West.

By the 1950s, during the golden age of Western television and movies, the Colt Peacemaker was a cultural icon. It featured prominently in the hands of characters played by actors like John Wayne, Gary Cooper, James Stewart, and Clint Eastwood. Though some of these productions were loose with historical accuracy, the revolver’s presence helped solidify its mythic status. For many Americans, and eventually for audiences around the world, the Colt Single Action Army became inseparable from the idea of rugged individualism, honor, justice, and the unforgiving code of the frontier.

Its influence extended into literature as well. Countless dime novels, pulp magazines, and later Western fiction treated the Peacemaker not just as a tool, but almost as a character in its own right. Guns were named, revered, and described with near-spiritual language, further enhancing their mythical allure.

Outside the realm of fiction, the Colt 1873 remained a popular choice among ranchers, farmers, and sportsmen well into the 20th century. It was reliable, simple to operate, and chambered in calibers that were readily available across rural America. Even as semi-automatic pistols gained ground in law enforcement and military use, the Peacemaker maintained a loyal following among those who appreciated its heritage and its handling characteristics.

The revolver’s mystique also drew attention from collectors, historians, and enthusiasts. Colt itself capitalized on this fascination by issuing commemorative models, limited-edition engravings, and reissues aimed at the civilian market. These modern productions paid homage to the original design while catering to the deep nostalgia that surrounded the Peacemaker.

Ultimately, the Colt Single Action Army transcended its role as a functional firearm. It became an emblem of a specific time, place, and ethos in American history. Whether resting in the holster of a frontier sheriff or gleaming from a display case in a collector’s home, the revolver spoke to ideals of freedom, responsibility, and unflinching resolve. Its carriers, real or imagined, were part of a story that continues to shape the American identity to this day.

The Decline, Rebirth, and Continued Influence of the Peacemaker

As the dawn of the twentieth century brought new developments in firearms technology, the Colt Single Action Army, once the pinnacle of sidearm design, began to show its age. While it remained a trusted and familiar weapon, it increasingly faced competition from more modern revolvers and the rise of semi-automatic pistols, which offered faster reloading, higher capacity, and double-action mechanisms that eliminated the need to manually cock the hammer for each shot.

The U.S. military formally replaced the Colt 1873 in 1892 with a double-action revolver chambered in .38 Long Colt. Though this new service revolver was mechanically more advanced, its stopping power paled in comparison to the .45 Colt, and reports from combat in the Philippines during the Moro Rebellion revealed its deficiencies. In many cases, soldiers found that the newer revolvers lacked the power to effectively stop determined attackers. This led to the temporary reissue of the old Colt Single Action Army revolvers from storage, a telling testament to the enduring respect for their power and reliability.

Colt continued manufacturing the Peacemaker for civilian sales into the early twentieth century, but production slowed as interest shifted toward newer designs. In 1941, with the United States entering World War II and Colt redirecting its industrial resources toward military arms production, the company officially ceased production of the Single Action Army. For a time, it seemed as though the revolver’s long career had finally come to an end.

But the Colt 1873 was not so easily consigned to history. In the years following World War II, a surge of interest in the American West swept through popular culture. Western novels, comic books, and most significantly, films, reintroduced audiences to the stories of frontier lawmen and gunslingers. The Western genre exploded in popularity, and with it came a renewed fascination with the firearms that defined that era. The Peacemaker, with its iconic lines and legendary reputation, was suddenly back in demand.

In response to this cultural resurgence, Colt resumed production of the Single Action Army in 1956, issuing what became known as the Second Generation models. These revolvers were faithful to the original design, with a few modernized manufacturing techniques, and were immediately embraced by collectors, sports shooters, and Western enthusiasts. A third generation followed in the 1970s, with additional updates to parts compatibility and production tooling.

During this revival, the revolver was not merely an artifact of nostalgia. It was also embraced by enthusiasts in cowboy action shooting competitions, where participants used period-accurate firearms and gear in timed marksmanship events modeled after frontier scenarios. In this context, the Colt 1873 remained not only viable but celebrated for its balance, accuracy, and mechanical charm.

Colt also capitalized on the renewed interest by producing a range of commemorative editions. These included engraved models honoring the U.S. Cavalry, the Texas Rangers, anniversaries of the revolver’s introduction, and even replicas of historic guns once owned by famous figures of the Old West. These limited-edition firearms were prized not only for their functionality but for their craftsmanship, historical ties, and collectible value.

Even as Colt’s own production fluctuated over the decades, the design remained in demand. Other manufacturers, including Uberti, Cimarron, and Ruger, produced their own versions of the Single Action Army, some near-perfect historical replicas, others modern reinterpretations. Ruger, in particular, offered ruggedized single-action revolvers inspired by the Peacemaker that featured coil springs, transfer bar safeties, and improved metallurgy, catering to a new generation of shooters while preserving the basic aesthetic of the original design.

The continued influence of the Colt Single Action Army can be felt far beyond shooting ranges and collector showcases. It remains a symbol of self-reliance and Americana, frequently appearing in films, television, artwork, advertising, and even political rhetoric. Its form—long barrel, flared grip, exposed hammer—immediately evokes a bygone era of personal justice and open landscapes, whether wielded by an actor in a Western or resting in a museum exhibit.

Today, more than 150 years after its debut, the Colt Peacemaker remains a living relic. It is studied by historians, cherished by collectors, used by enthusiasts, and admired by anyone with an interest in American history. Though it was born of a specific time and need, its influence has proved timeless. Few firearms have bridged the gap between practical utility and cultural icon as successfully as the Colt Single Action Army. It is not merely remembered—it continues to be experienced, passed down, and revered.

Denix Replicas and the Preservation of Form

Denix 1873 Non-Firing Replica With Faux Ivory Grips

As original Colt Single Action Army revolvers became historical artifacts and valuable collector’s items, there emerged a growing demand for accessible, accurate reproductions that could serve educational, theatrical, and decorative purposes. Among the companies that answered this demand, Denix of Spain has established itself as a leading manufacturer of non-firing replica firearms. Through its extensive catalog, Denix offers a faithful visual recreation of the 1873 Peacemaker, allowing enthusiasts to own a piece of history without the costs, restrictions, or legal considerations that accompany authentic firearms.

Denix replicas are not functional weapons. They are made from cast metal alloys and finished with wood or imitation ivory grips, depending on the model. These materials are chosen for their durability and appearance, creating a convincing illusion of the original without the mechanical components required to chamber or fire live or blank ammunition. The result is a non-lethal, safe-to-handle object that retains the shape, size, and weight balance of the historical revolver.

Among the most popular models available through us here at TCN Vault is the Denix 1106G, which replicates the civilian-style 1873 with a 5.5-inch barrel and wooden grips. The cylinder rotates, the hammer cocks and releases, and the trigger articulates with realistic resistance, all of which contribute to an authentic feel in the hand. Other models replicate cavalry-length barrels or showcase ornate design elements reminiscent of presentation-grade revolvers from the late 19th century.

Collectors and historical enthusiasts have praised Denix replicas for their visual fidelity. The screw placement, barrel taper, frame shape, and general proportions are all carefully rendered. While there is no internal firing mechanism, many models include mock cylinders that allow the user to insert dummy rounds, enhancing the realism for display or staged use.

These replicas have become particularly important for historical reenactments, where the appearance of authenticity is crucial but the use of live or blank-firing weapons is impractical or restricted. Film productions and theatrical performances also benefit from the use of Denix replicas, as they allow actors to handle and draw what appears to be a real revolver with no risk to the cast or crew.

In addition to their visual and tactile qualities, Denix replicas help preserve a sense of historical awareness. Not everyone can afford or legally possess an original Colt Single Action Army, but a Denix replica offers an opportunity to experience the weight and design of the revolver that helped shape American history. It is a way to study, admire, and display a formative piece of technology without the obligations that come with actual firearm ownership.

Denix has found a niche in the growing market of replica arms, and its 1873 revolvers have become a cornerstone of that success. They are not tools for the range or combat training, but they are accurate, accessible, and safe. In doing so, they keep the form and feel of the Peacemaker alive for generations who may never hold the real thing.

Bruni Blank-Firing Replicas and the Revival of Function

Bruni Old West 1873 Blank Firing Revolver Gun

While non-firing replicas like those produced by Denix serve as excellent tools for education, collection, and theatrical display, there remains a separate category of reproductions designed to simulate not just the appearance but also the audible and mechanical function of a real firearm. Among the most prominent manufacturers in this space is Bruni, an Italian company known for producing blank-firing firearms that closely replicate the form and operation of classic revolvers, including the legendary 1873 Peacemaker.

Bruni’s replicas are engineered to fire blank cartridges—ammunition that contains gunpowder but no projectile. When discharged, these rounds produce the sound, recoil, and flash associated with live ammunition, but without the danger of a bullet leaving the barrel. Because of this, blank-firing guns occupy a unique position in the world of replicas. They offer a heightened sense of realism without the legal and safety concerns associated with live-firing weapons.

The Bruni 1873 models mimic the mechanical operation of the original Colt Single Action Army with remarkable accuracy. Users must manually cock the hammer before each shot, just as with the original single-action design. When the trigger is pulled, the hammer drops, striking a firing pin that ignites the primer of a blank cartridge. The cylinder rotates in the same manner as the historic revolver, and the sounds and movements produced are strikingly similar to those of the real thing.

For filmmakers, reenactors, and trainers, this level of authenticity is invaluable. The loud report, visible muzzle flash, and mechanical cycling of a Bruni revolver add a dimension of realism that is impossible to achieve with inert replicas. Actors can interact with the revolver in a way that mimics true firearm handling, and instructors can use blank-firing models in controlled environments to acclimate students to the sound and behavior of gunfire without the associated risks.

Bruni’s replicas are also widely appreciated for their craftsmanship. Most models are constructed from steel or durable zinc alloy and finished in black, blued, or nickel plating, with grips made from wood or imitation ivory. The dimensions and weight are carefully calibrated to match the original Colt 1873, ensuring an authentic feel in the hand.

However, because they are capable of firing blank ammunition, Bruni revolvers are subject to a different set of legal restrictions than non-firing replicas. Ownership laws vary by country and, in some cases, by state or municipality. In many jurisdictions, these blank-firing models are treated as restricted items, even though they cannot fire live ammunition. Bruni revolvers are also built with internal design modifications—such as obstructed barrels and unique firing pin configurations—that make it physically impossible to convert them to fire live rounds.

This attention to safety engineering has made Bruni a trusted name in the industry, but it also underscores the importance of proper handling. While blank rounds do not launch projectiles, they can still cause harm at close range, particularly due to muzzle blast and hot gases. For this reason, Bruni revolvers should always be treated with respect and used only in accordance with safety guidelines and local regulations.

Blank-firing replicas like those produced by Bruni occupy a distinct place in the continuum of historical firearms preservation. They bring back not just the image of the past, but also its sound and rhythm. In a film or live demonstration, a Bruni revolver evokes the sharp crack of gunfire, the smoke curling from a barrel, and the deliberate mechanics of a single-action draw. It bridges the divide between theater and authenticity, offering an immersive experience of history that is both dramatic and instructive.

Comparing the Replicas to the Original

As the Colt Single Action Army aged into legend, it became more than a firearm. It became a physical representation of an era, a mechanical relic that embodied the spirit of the American frontier. Today, as original Peacemakers become increasingly rare and valuable, replicas like those produced by Denix and Bruni offer a way to preserve and interact with that legacy. While neither of these reproductions can fully replicate the function of a real 1873 Colt, each offers distinct qualities that echo the original in meaningful ways.

The Denix replicas are designed to capture the shape, size, and external mechanics of the Colt 1873 without functioning as real weapons. These replicas are solidly built from cast metal and fitted with wooden or simulated ivory grips. They replicate the revolver’s proportions with considerable accuracy, including the curvature of the grip, the angles of the frame, the placement of the loading gate, and the rotation of the cylinder. The hammer and trigger move, giving the user a tactile impression of the original single-action mechanism. However, the internal workings are simplified, and the cylinder chambers are non-functional. These replicas cannot be loaded with real ammunition, and they are not designed to fire in any capacity.

By contrast, the Bruni models are intended to fire blank cartridges. This places them closer in operation to the original Colt Single Action Army. The hammer must be cocked manually before each shot, the cylinder rotates with each trigger pull, and the revolver produces the report and flash of a real gun. These elements make the Bruni models particularly valuable for theatrical and training use, where sound and realism are critical. Bruni revolvers are manufactured with internal safety features that prevent them from being converted to fire live ammunition. Despite these safety modifications, they offer a more immersive experience, complete with recoil, smoke, and mechanical function.

Both replicas are visually faithful to the original, and both are typically made to the same dimensions. The weight of a Denix model is often close to that of a real Colt, giving it the correct balance when held. Bruni models, with their added internal components, may feel slightly heavier or more robust, but they still maintain the overall feel of a frontier revolver. In terms of finish, both manufacturers offer options that reflect historical appearances, from blued barrels and brass frames to nickel plating and custom-style grips.

Where the two replicas differ most dramatically is in their purpose. A Denix revolver is best suited for display, reenactment, or educational use. It can be safely handled by people of all ages, requires no special permits or legal considerations in most areas, and poses no risk when used as a prop. Bruni revolvers, on the other hand, require careful handling and often fall under specific regulations. They are capable of discharging blanks and should be treated with the same caution as any firearm. They are ideally suited for staged performances, law enforcement training, or immersive historical interpretation.

Neither Denix nor Bruni seeks to replicate the full craftsmanship of a 19th-century Colt revolver. The original Single Action Army was built with the precision of hand-fitted parts, forged steel, and attention to detail that reflected the standards of its time. While modern manufacturing makes replicas affordable and widely available, it also means certain compromises are inevitable. The feel of a trigger pull, the tightness of the lockup, or the weight of a finely machined steel cylinder cannot be perfectly reproduced in mass-market replicas.

Still, the core of the Colt 1873 lives on in these models. The handling characteristics, visual presence, and symbolic value are preserved. For collectors, filmmakers, reenactors, or those simply fascinated by American history, Denix and Bruni offer two ways to engage with the legacy of the Peacemaker. One preserves its appearance and mechanical layout. The other revives its dramatic effect. Each in its own way carries forward the memory of a revolver that helped define a nation’s image of itself.

The Modern Role of Replicas and the Living Legacy of the Peacemaker

In the present day, more than a century and a half after its introduction, the Colt Single Action Army remains one of the most recognized and revered firearms in the world. Though few modern shooters carry the original revolver into the field or onto the range, its image continues to command attention. The Peacemaker has become something greater than a tool of war or personal defense. It has become a cultural icon, and its replicas serve as tangible reminders of the role it once played in shaping the identity of a nation.

Replicas like those produced by Denix and Bruni allow people from all walks of life to experience the Peacemaker in meaningful ways. For some, the value lies in physical presence alone. A non-firing replica can be held, studied, displayed, or incorporated into costume and reenactment with no risk or restriction. It offers an educational opportunity for classrooms, museums, and public demonstrations, where the goal is to teach history without the hazards of a live firearm. These replicas also serve collectors who appreciate the visual and tactile qualities of 19th-century sidearms but may lack access to an original or prefer the safety and affordability of a reproduction.

For others, the appeal lies in realism. Bruni’s blank-firing revolvers introduce movement, sound, and energy to the experience. A staged duel, a training exercise, or a film set becomes more authentic when the sharp crack of a blank round echoes in the air. The revolver jumps in the hand, the hammer falls, and smoke curls from the muzzle. In those moments, history is not just remembered. It is performed.

Both types of replicas serve a modern purpose that extends beyond nostalgia. They function as bridges between generations, helping to carry forward stories that might otherwise fade into the background of textbooks and movie scripts. A Denix replica in a display case invites questions about who carried the real thing and what kind of world they lived in. A Bruni model used in a historical reenactment re-creates the sounds and gestures of a distant time, allowing audiences to experience something that feels immediate and real.

At the same time, these replicas provoke reflection. They remind us that firearms like the Colt 1873 were not simply tools of defense or offense, but instruments of policy, expansion, personal identity, and cultural transformation. They were held by soldiers, marshals, outlaws, homesteaders, and ranch hands. They figured into legal proceedings and lawless shootouts, domestic defense and violent crime, personal survival and public theater. They were deeply embedded in the moral complexity of a young and rapidly changing country.

The continued fascination with the Peacemaker reflects something persistent in the American imagination. It is a fascination with independence and justice, with the right to protect oneself, with the ability to navigate a vast and sometimes dangerous world on one’s own terms. The revolver, in this sense, becomes more than steel and powder. It becomes a metaphor for self-determination and personal responsibility.

In the end, the enduring legacy of the Colt Single Action Army is found not just in museums or gun safes but in the hands of those who carry on its story. Whether through a non-firing replica displayed on a mantel or a blank-firing revolver used to reenact a frontier skirmish, the Peacemaker continues to live, not as a relic, but as a living symbol. It survives through memory, motion, and meaning. And in that survival, it still speaks to the past, not as a whisper, but with the full weight of history in its echo.